Listening to the ancient world beneath our feet

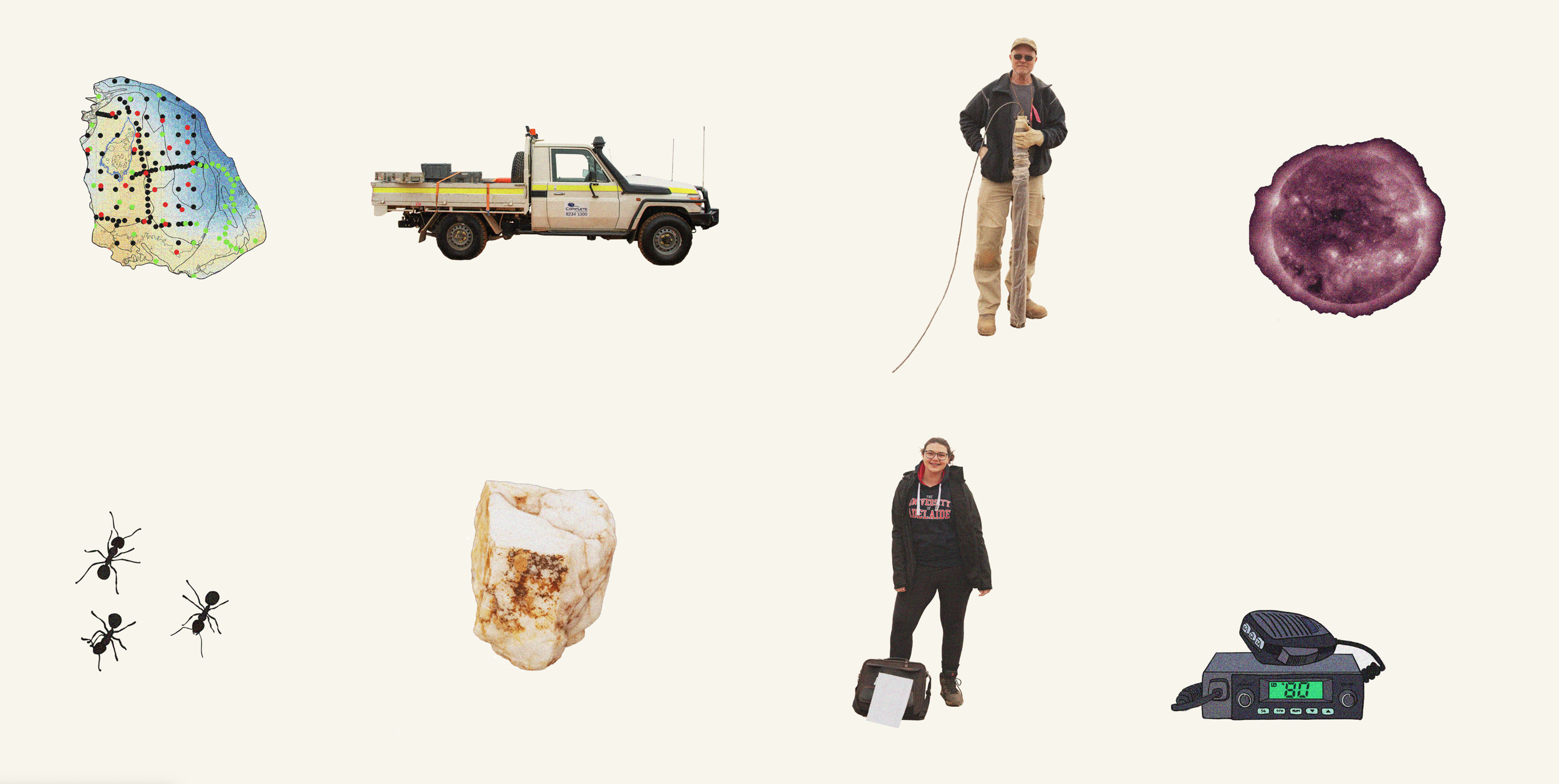

Laying out the MT. Image: Jarred Llyod

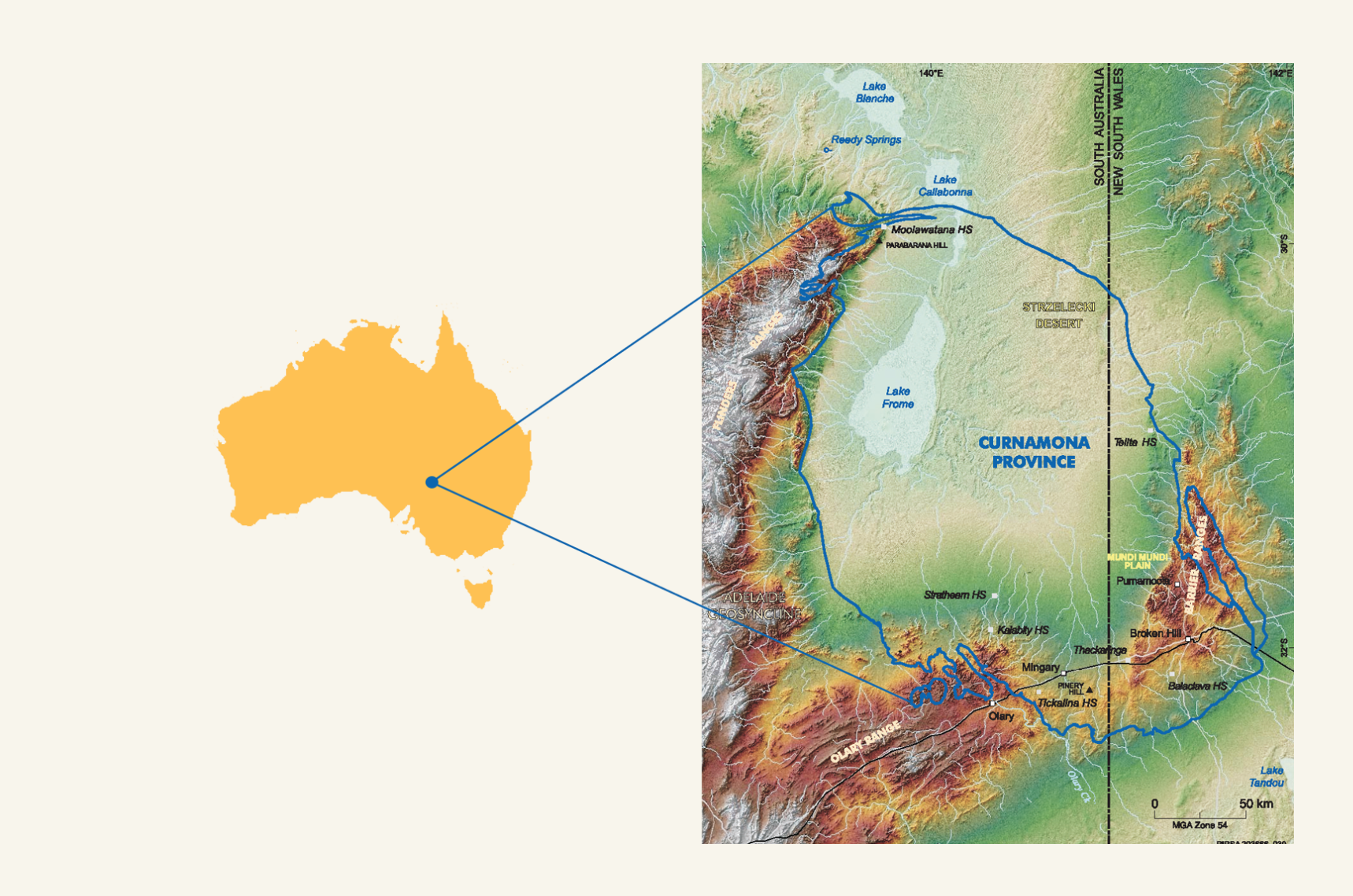

At the border of South Australia and New South Wales lies the Curnamona Province, a region that holds an untold story about Earth’s evolution over billions of years. By using NCRIS-enabled infrastructure, researchers are building a detailed 3D model of the Province, known as the ‘Curnamona Cube.’ The Cube reveals the hidden geological history of our planet and how ancient supercontinents came together to form the world as we know it today – all without ever breaking ground.

The challenge

In a landscape so still that you can hear your own breath, researchers are listening not with their ears, but with scientific instruments attuned to the murmurs of the ancient world beneath our feet.

Straddling the border of South Australia and New South Wales lies a geological treasure trove: the Curnamona Province. To most, it’s an arid and remote expanse, home to small mining towns like Broken Hill, with rich deposits of zinc, lead and silver. But to geoscientists like Professor Graham Heinson, it’s much more than that. It’s a time capsule that hides an untold story of how our planet has evolved over billions of years.

However, caught between state borders and roughly the same size as Tasmania, the region isn’t easy to study.

“It’s an area that’s had very little attention. It’s remote, difficult to get to, and covered in thick layers of sediment,” said Graham, “there’s a lot of history hidden beneath the sedimentary cover.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

And that’s exactly why he went there.

A 3D visualisation of the deep Earth

Based at the University of Adelaide, Graham and his research team embarked on a mission to uncover the hidden geology of the Curnamona Province.

Their goal was to construct a detailed, 3D model of the Earth’s crust and upper mantle – a ‘cube’ spanning roughly 400 km in length, 400 km across, and 200 km deep beneath the Earth’s surface. They dubbed it the ‘Curnamona Cube.’

But the researchers didn’t develop the Cube by drilling or digging. Instead, they listened.

They installed over 135 seismometers across the Curnamona Province, spaced about 25 km apart, to ‘listen’ for subtle vibrations beneath the Earth’s surface. Seismometers detect vibrations many orders of magnitude lower than what is detectable by humans, caused by small earthquakes from around the world, or swells at the coastline hundreds of kilometres away.

“We’re listening to the Earth on a very small scale, listening to sounds that no one could hear.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

By analysing how fast the waves travel between seismometers, the researchers can gain insights into rock composition and structure.

“If you bump the Earth in one place, there's a sort of wave that travels out. It’s like throwing a stone into a pond, and you can see the ripples going out in all directions. The speed at which the wave travels between each pair of seismometers depends on how strong and hard the rock is between those two seismometers. If it's very rigid and strong, then the seismic wave travels very quickly. But if the rock is loose, then it travels much more slowly.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

The researchers also deployed magnetotelluric (MT) instruments that measure changes in the Earth’s electromagnetic fields, induced by things like solar flares and lightning. When lightning strikes move through the Earth, they generate electric currents, which can be measured using MT instruments.

These instruments consist of a long wire with electrodes at the end that can measure electrical currents at microvolt resolutions, 1 billion times smaller than a volt. This provides information about electrical resistivity – another proxy to understand the structure and composition of the Earth’s crust.

“The amount of current flowing through depends on a property called ‘electrical resistivity,’ and that, in turn, depends on things like how much salt water is present, whether there are any minerals, the temperature, and the chemistry of the rock,” said Graham. “What that tells us is something of the history of the Earth, how the different parts joined together and where they joined, because they have different chemistry and properties.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

Together with other geophysical data, these measurements enabled Graham and his team to peer hundreds of kilometres beneath the Earth’s surface to reconstruct a rich, high-resolution model of the Curnamona’s internal structure.

A new understanding of Earth’s evolution

“Below the topography and down to 400 km, we show electrical resistivity; red colours show zones that conduct electricity well, blue regions are insulators. Like a dice, we can spin the cube to show various faces, slice the cube along faces, and can restrict views to just smaller ranges of values. “

- Professor Graham Heinson

The findings, which were recently published in Tectonophysics and Gondwana Research, revealed interesting insights into how this ancient part of the continent has shifted and evolved over billions of years.

“What we found is two joins of continents. One of them is in an area close to the middle of the Curnamona – the really old bits of the continent that joined together. The middle and the edge are from a little bit later, when the eastern side of Australia joined on. They’re sort of like jigsaw pieces that have been in the Earth for between 500 million years and 2 billion years. It preserves a record of that history.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

Other members of the geoscience community, such as researchers and industry professionals, can use the data from the Cube to see more clearly and deeply into the Earth than ever before, aiding in critical minerals and geothermal energy exploration.

AuScope: a decade of supporting research in the Curnamona Province

AuScope played a pivotal role in supporting this research by enabling the deployment of the seismic and MT instruments and providing the critical infrastructure needed for data processing and analysis.

“AuScope has been transformative. We would never have been able to do anything like this without their support,” said Graham, “As well as providing instruments, data and resources, AuScope also supports the development of a new generation of research staff. It's an investment in infrastructure, but it's also an investment in talent and mentoring.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

Reflecting on the research, Graham said he felt privileged to help others see the Earth in a way that no one had ever seen it before.

“There’s a great beauty in the Earth, and in telling its story. It’s a sense of awe when we approach some of these scientific projects. But in addition to the natural beauty of it all, is curiosity. That’s what drives a lot of our fundamental research.”

– Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

By quietly listening to the murmurs beneath our feet, the Curnamona Cube is a reminder that sometimes, the most powerful discoveries come when we stop to hear what the Earth has been saying all along.

Accessing and exploring the Curnamona data

Researchers, students, and industry partners can explore the Curnamona Cube datasets (as released) and related geophysical information through AuScope’s NCRIS-enabled national data infrastructure.

Seismic and Magnetotelluric (MT) data are available via AusPASS (Australian Passive Seismic Server).

For a more general audience, we have our Immersive Earth website where you can explore the sights and sounds of work in the field.

Visit our Immersive Earth website to dive deeper.

Contact Information

Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide | graham.heinson@adelaide.edu.au

Case Study

Led by Professor Graham Heinson and supported by NCRIS-enabled infrastructure, researchers created the ‘Curnamona Cube’ – a 3D model of the deep Earth – to advance our understanding of continental evolution and aid exploration for critical resources.

Author

Dr Cintya Dharmayanti, Scientell

PEER-REVIEWED PAPER

Tectonophysics – Crustal structure of the Curnamona Province in Australia by ambient noise tomography. Published online 5 April 2025. DOI

Gondwana Research - Lithospheric architecture of the Curnamona Province, Australia. Published online 5 May 2025. DOI

Key People and Organisations

Professor Graham Heinson, University of Adelaide

Dr Ben Kay, AuScope